Particularly susceptible to global warming, Arctic regions are seeing their frozen soils melt at an accelerating rate. As a consequence, when thawing, permafrost releases organic matter that produces CO2 and CH4 via bacterial activity. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a ‘climate bomb’ because it could significantly increase anthropogenic global warming, to an extent that is still poorly understood.

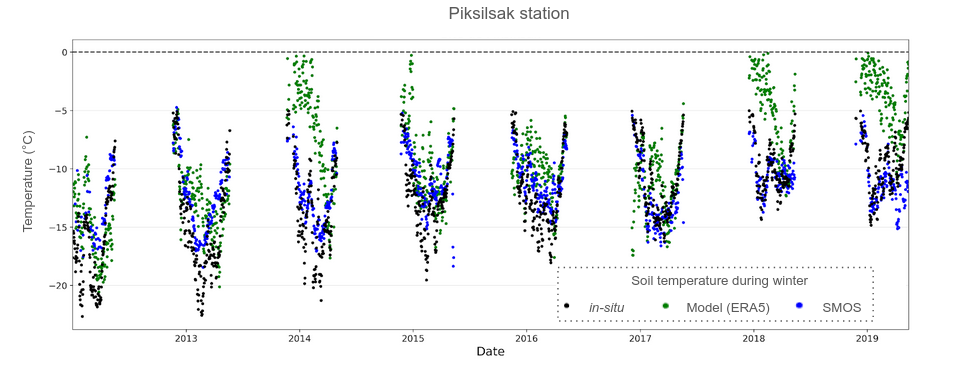

Monitoring permafrost is therefore extremely important, but faces a major obstacle: the presence of snow on the surface in winter. Snow is opaque to many frequencies, which complicates satellite remote sensing studies. However, the L-band (1.4 GHz) used by the SMOS satellite can penetrate snow and detect ground emissions. By refining a physical model, J. Ortet was able to obtain the first global measurements of surface temperature under the snowpack from SMOS’s brightness temperatures. These results match well with field data in regions where lake coverage is limited:

These new estimates should help understanding the role of vegetation in the spatial distribution of soil temperature. Snow cover is an insulator, of course, but its insulating properties vary depending on the presence of vegetation, which could act as a thermal bridge. Indeed, a study made in two sites showed that when shrubs are embedded in the snow, the heat exchange between the air and the ground is facilitated, making soil 1.2°C colder in early winter and 5°C warmer in late winter. These observations seem to confirm such hypothesis across the Arctic, but more research is under way…

More information on the newly published article : here !